The Indigenous Inhabitants of the Area

The original indigenous inhabitants of the region were the San and Namas. They did not see themselves as different ethnic groups. The social structure and languages of the two groups shows great similarity. They both speak languages which is remarkable in the prevalence of click consonants. The Namas are part of the indigenous people who called themselves Khoikhoin, which can be translated as men of men or real human beings. They draw a clear distinction between themselves and the San whom they saw as a property less class of people.

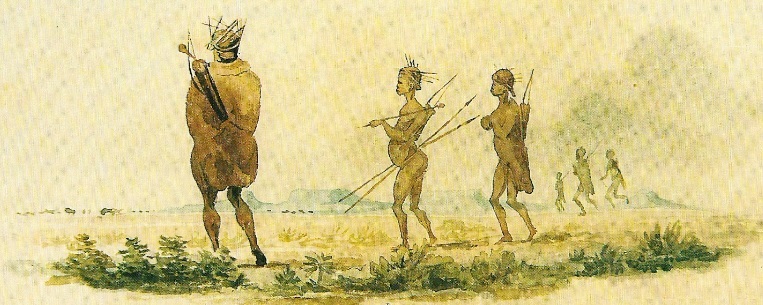

San

The San led a nomadic life as hunters and gatherers. They lived of the hunting of game and collection of edible plant and animal products. They lived in harmony with their natural environment and did not stay in permanent dwellings but lived in caves or poorly constructed temporary shelters. They roamed the area as small hunting groups who sometimes clashed with the Nama. The San did not seem to have any general or collective name for themselves. The word San is derived from a Nama word “sa”, which means to settle, reside or rest. San can therefore be translated as original inhabitant. The word San has a negative meaning in the Nama language. The Nama did not see the San as a different ethnic group, but as a lower social class that don’t own livestock.

The Dutch settlers in called them by names like Bosjemens, Bosmanekens or Bosiesmans, from which the name Bushmen was later derived.

Namaqua

The second indigenous group who lived in the area was the Nama. They are part of the Khoikhoi, who call themselves the men of men or real people to distinguish themselves from the San, who were living of the veld and who had no cattle. The Nama were nomadic stock farmers, who moved around with their livestock with the changing of seasons in search of gracing and water resources. The Nama lived within a certain territory as nomads. They lived in reed houses which they called /haru oms. These houses were the ideal structure for their nomadic life, because it is simple to dismantle, carry on the backs of oxen and erect it somewhere else. The Nama were organised into smaller social units with a chief as head. The chief ruled jointly with the other male heads of families, who made up the tribal council.

According to the historian, Elizabeth Trüper, cattle was very important in the social lives of the Nama: “With the Nama, their cattle were the central measure of wealth and the foundation of their social reputation. Rich cattle owners were able to secure their followers’ loyalty because they were allowed to keep a part of the proceeds of the herd and also of the new-born animals. If somebody lost their cattle through theft or sickness, he was able to earn a new herd. In general, a man or woman would not be permanently without property in Nama society.”

TIMELINE OF THE HISTORY OF STEINKOPF

1817 – Establishment of the Steinkopf Mission Station at Besondermeid by the London Missionary Society

1838 – The headquarters of the mission station moved to Kookfontein

1840 – The London Missionary Society terminated their work at Steinkopf

1840 – The mission work is taken over by the Rhenish Missionary Society

1847 – Steinkopf became part of the Cape Colony

1848 – The death of the last local Nama chief Vigiland Orlam

1850 – The commercial mining of copper in Namaqualand

1876 – The railway line of the copper train between Port Nolloth and the copper mines reached Steinkopf

1902 – The Boers invaded Steinkopf during the Anglo-Boer War

1913 – The 1909 Mission Stations and Communal Reserves Act introduced direct government rule in Steinkopf

1934 – The Dutch Reformed Mission Church took over mission work at Steinkopf

1948 – The Government introduced the apartheid system which formally declared Steinkopf as a Coloured Rural Area

1994 – The First Democratic Elections in South Africa

2000 – Steinkopf became part of the Nama Khoi Municipality

In 1840 the London Missionary Society transferred its work in Namaqualand to the Rhenish Mission Society, a German organisation. For the first few years no missionary was stationed at Steinkopf and the mission station was served by visiting missionaries from Komaggas. In 1846 the Rev. Ferdinand Brecher, who was to stay at Steinkopf for about fifty years, start to work as missionary in the community.

Elfrede Strassberger reported on the work of the Rev. Brecher:

“Brecher found sixty people who had been at Kookfontein, where the old Captain Abraham (Vigiland Orlam was called Abraham after his baptism as Christian) and his wife (Sarah) received him with great joy. The number of baptised persons soon increased to 300. The congregation was scattered over 1600 square miles. They were constantly moving. Brecher endeavoured to persuade them to live a settled life. He encouraged agriculture and the cultivation of grain and other crops. He built a church, a school and a mission house. At Christmas time he assembled the congregation to celebrate the festivities. After the celebrations they once more dispersed in all directions.

This made his work very difficult.”

Rev. Brecher’s term as missionary also saw some important changes Steinkopf. The first of these was the extension of the boundary the Cape Colony to the Orange River in 1847 and Steinkopf was now under colonial rule and the people became British subjects. Around 1850 commercial mining of copper also started in Namaqualand which had a huge impact on the mission station at Steinkopf. Local residents benefitted from income of work on the mines and the transporting of copper. In 1873 the copper railway line was completed to Steinkopf and the town had its own railway station. More cash was available and new developments came to the community. Some people started to build better houses, the income of the mission increase and congregation became more self-supporting. The work at the mines also led to neglect of the farming, increase substance abuse and an increase of dependence of local shops. A mine was also open on the farm Tweefontein, which was part of Steinkopf Mission Station which led to the development of a mining town called Concordia.

The wars during the turn of the 19th to 20th century also did not leave Steinkopf untouched. Steinkopf became part of the Anglo-Boer War when a large force of Boers invaded Namaqualand in 1901. Martial Law was proclaimed throughout the district. About 100 men form the community joined the English military forces as volunteers. They were part of the Town Guards and Namaqualand Border Scouts. Steinkopf was invaded by the Boers in April 1902 and local people fled by train to Port Nolloth where they stayed in refugee camps. The siege of Steinkopf ended on the 1st of May 1902 when the Boers left the town after heavy fighting against the British relief forces.

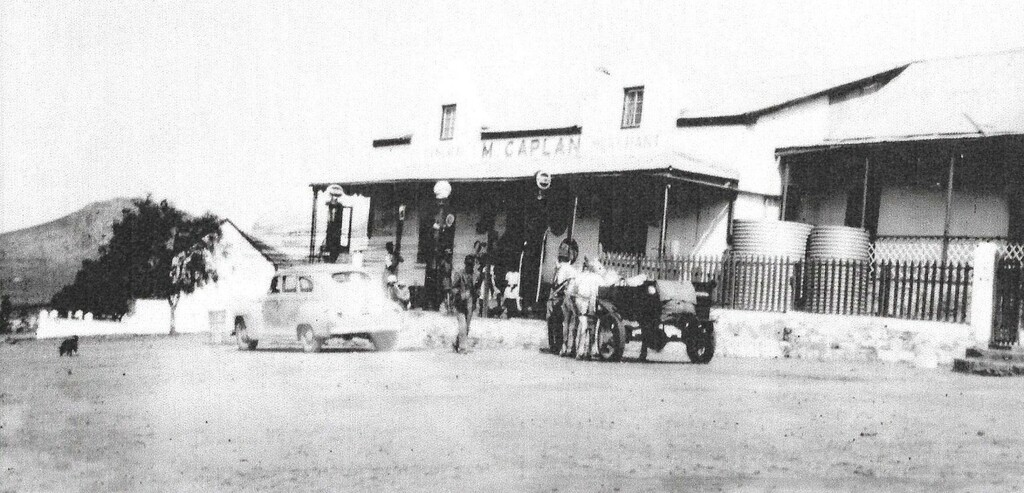

The money economy in Steinkopf started in 1887, when first trading licenses were issued by the Community Council. They were issued to German traders including the Brecher family. After 1900 several Jewish businesspeople also settled in Steinkopf, like elsewhere in Namaqualand. Several of them wer shop owners will some of them also became involved in prospecting and mining. These Jews left Steinkopf after the introduction of apartheid when Steinkopf was declared a Coloured Rural Area and they were forced to leave.

A second war that impact on the community of Steinkopf was the battles between the German colonial forces and the indigenous Nama and Herero’s from 1903 to 1906 in neighbouring Namibia, then called German Southwest Africa. Military resources were imported through the railway line and transported from Steinkopf across the Orange River. Local people benefitted from the transport riding of these goods to Namibia. After the war more then 600 people crossed the Orange River as refugees and stayed for a few months outside Steinkopf. Because the local authorities at Steinkopf did not want to give them shelter they were placed in a refugee camp at the Roman Catholic Mission Station at Matjieskloof. The local councillors, who was Basters, did not want to allow such a large group of Nama in Steinkopf because they were afraid that they would lose political control in the community.

In 1910 the Union of South Africa was formed when the colonies of Natal and the Cape, joined forces with the two Boer republics, Transvaal and Orange Free State, to form a white dominated South African state. This was one of the major forms of betrayal of the British against their previous allies when they joined forces with their former enemies during the Anglo-Boer War. In Steinkopf the impact of this unholy alliance was the introduction of the 1909 Mission Stations and Communal Reserve Act which brought direct government control over the community. The old Community Council was desolved and the church lost its control over community affairs. A Board of Control consisting of local councillors and chaired by the magistrate from Springbok replaced it.

During the 1st World War, 1914 – 1919, many troops and supplies through Steinkopf during the earlier phase of the War when German Southwest Africa was invaded. Many local also participated in the war as soldiers both in South Africa and abroad. The local missionary, the Rev. Kling, was interned and send to Pietermaritzburg during this war because he was a German citizen.

When diamond mining started in the 1920’s on the west coast of Namaqualand at places like Kleinzee and Alexander Bay, people from Steinkopf went to the mines as migrant workers. This was an economic relationship between Steinkopf and the diamond mines which lasted for most of the 20th and into the 21st century.

The Rhenish Mission Society ended their work in Steinkopf in 1934 because of financial challenges and transfer the mission work to the Dutch Reformed Church. This brought an end to about 94 years of service to the community and of German influence in Steinkopf.

The church was the first church building in Steinkopf and was completed in 1849 in the time of rev. Ferdinand Brecher as missionary.

The mission house was completed in 1855 but was destroyed by a fire in November 1868. A new and larger house was constructed, but all the church records was destroyed by the fire. The government surveyor, Robert Moffat, who visited Steinkopf in 1855, did not give a give picture of the mission station: “I was surprised by the wretched appearance of the station, which certainly does not betoken progress in the people. Saw only a mission house and chapel, the latter a very pretty building. There were two outhouses belonging to Bastards, one resembling a farmer’s kitchen or rondawel. There was also a sort of garden, walled in. The fountain or spring a miserable affair. If properly attended to, the place might be much improved.”

Before the railway line between Port Nolloth and the copper mines was completed copper was transport by wagons from the mines to the coast for export. Many local men made a living from transport riding during, which brought cash income to residents. Steinkopf became part of the cash economy which was brought to the country by the European settlers. The government geologist, E.J. Dunn, who visited Steinkopf in the 1880’s reported as follows: “About ten miles from Anenous the mission station of Kookfontein stands. Kookfontein is fast developing into a village, with ‘winkels’ and substantially built dwelling-houses.” The sketch shows the church, the new buildings, transport wagons and that most residents still lived in the traditional mat houses.

The soldiers on horses are Jan Smuts and his men, a Boer general and later prime minister of South Africa, who travelled through Steinkopf during the Anglo-Boer War. At that time Steinkopf was under siege by the Boers, April 1902. Local people left the town to go and stay in refugee camps at Port Nolloth. More than one hundred local men participated as volunteers on the side of the British Field Forces in Namaqualand. The siege of Steinkopf only ended after fierce fighting between the Boers and the British Relief Forces who were based at Klipfontein.

Established in 1945

After this community co-operative was established it became the only local shop and replaced the systems of local shops previously owned only by White business people, mostly Jewish shop owners.

It exists until 1990 when it was declared bankrupt.

Nowadays it is owned by private business. Today known as OK Foods

The first Jews settled at Steinkopf as businesspeople shortly after the Anglo-Boer War. Except the trading business some of them were also involved in prospecting and mining ventures. Some local people acquired considerable knowledge and mining techniques from these people. They started to due their own kind of mining which concerned the working of a small scale of the patches of mineral deposits, chiefly beryllium and scheelite, found in the mountains to the north of Steinkopf. The minerals mined in this way were sold to the Jewish traders. Most Jewish business people left Steinkopf in the 1940’s because of the introduction of apartheid laws and refusal of the local Management Board to renew their trading licenses.

The anthropologist Peter Carstens who published this photograph described describe Steinkopf of those years as: “Here is the church and the missionary, the seat of local government where the law is administered and taxes paid; here are the main schools, including the only secondary school for Coloured people in Namaqualand, with its new library; here are the shops and the granary and the police-station; here you will find a weekly cinema and the clinic with a trained midwife ; its here that people are baptised, married and buried. Here is the centre of interaction with the outside world, the place where new ideas and fashions are disseminated, spreading outwards to the conservative settlements.

The true dorpenare (villagers) are those who live permanently in the mission village and co-operate in its social live – the teachers, shopkeepers and shop assistants, the few administrators, the various categories of tradesmen and workers, pensioners and others. But these constitute only about a quarter of the potential village population of approximately 2000 people; the remainder cannot be classed as true villagers for, although they may spend most of the year in the village, they are engaged also in other activities on their farms.”

"Original photo in black and white this one has been colorized"

.

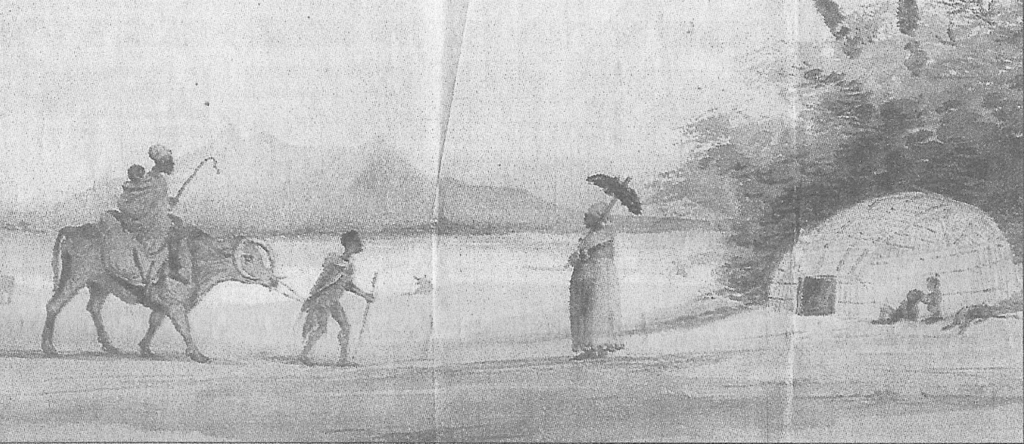

The sketch illustrates that the Namaqua were stock farmers who kept cattle, goats and sheep and lived in the typical beehive shaped mat houses, called /ura oms in the Nama language. The quiver tree shown in the drawing, an indigenous succulent of the Namaqualand, can still be seen in the Steinkopf area.

Namaqua Settlement in the 18th century

Drawing of the Namaqua people made by Charles D.Bell

It illustrates the uses of cattle as riding animals and the typical mat house. Cattle were important in the culture of the Namaqua. Their food consists of milk and meat from hunting and domestic animals augmented with edible plants and animal products collected in the veld, called “veldkos”.

Charles D. Bell was a man of many talents who visited Namaqualand in the 1830’s when he made these drawings. In 1848 he was appointed surveyor-general of the Cape Colonial government. He visited Namaqualand and Steinkopf, in 1854. He said the following of the people of Steinkopf, which he called “Kookfontein” and their land rights: “Their right of occupation of the ground rested on the rights allocated by the old chiefs of the Little Namaquas or by the Namaqua right from time immemorial, which occupation was in force at the time of the annexation of their country.”

Most of this history on this page work has been obtained from the research done by Mr. J.F.van Wyk